Part of the Problem

Originally published in the RISD Graphic Design Triennial publication, October 2018

Since the advent of mechanical reproduction, we have inundated our planet with combinations of Type and Image, or what we loosely now call “Graphic Design.” (Let’s just say design.) In this century, the amount of design that reaches our eyeballs on a daily basis has increased exponentially, and the stakes of this onslaught on our contemporary culture are high. Design theorist Tony Fry argues that design is unambiguously, profoundly political, in that it wields the power to either “serve or subvert the status quo.”

Building one’s design practice in 2018, a designer must question: How much of all that design, in text and subtext, subverted the status quo? Or, chillingly: how much of that unquantifiable sum was the dutiful servant of white supremacy, colonialism, hetero/cisnormativity, ableism, and misogyny?

There is power in Type and Image — and if the world is broken in 2018, design helped make it so.

There is a robust history of design contributing to dissent, and credit is due to the many designers who have centered their practice in fighting injustice. Where we have repeatedly fallen short is to take responsibility for reinforcing a culture that is unjust. We must stop pretending that we haven’t been a part of the problem all along. We have neglected this obligation for decades.

The need for the field of design to be critical — of itself, its patrons, its audience, and systems of power — is paramount.

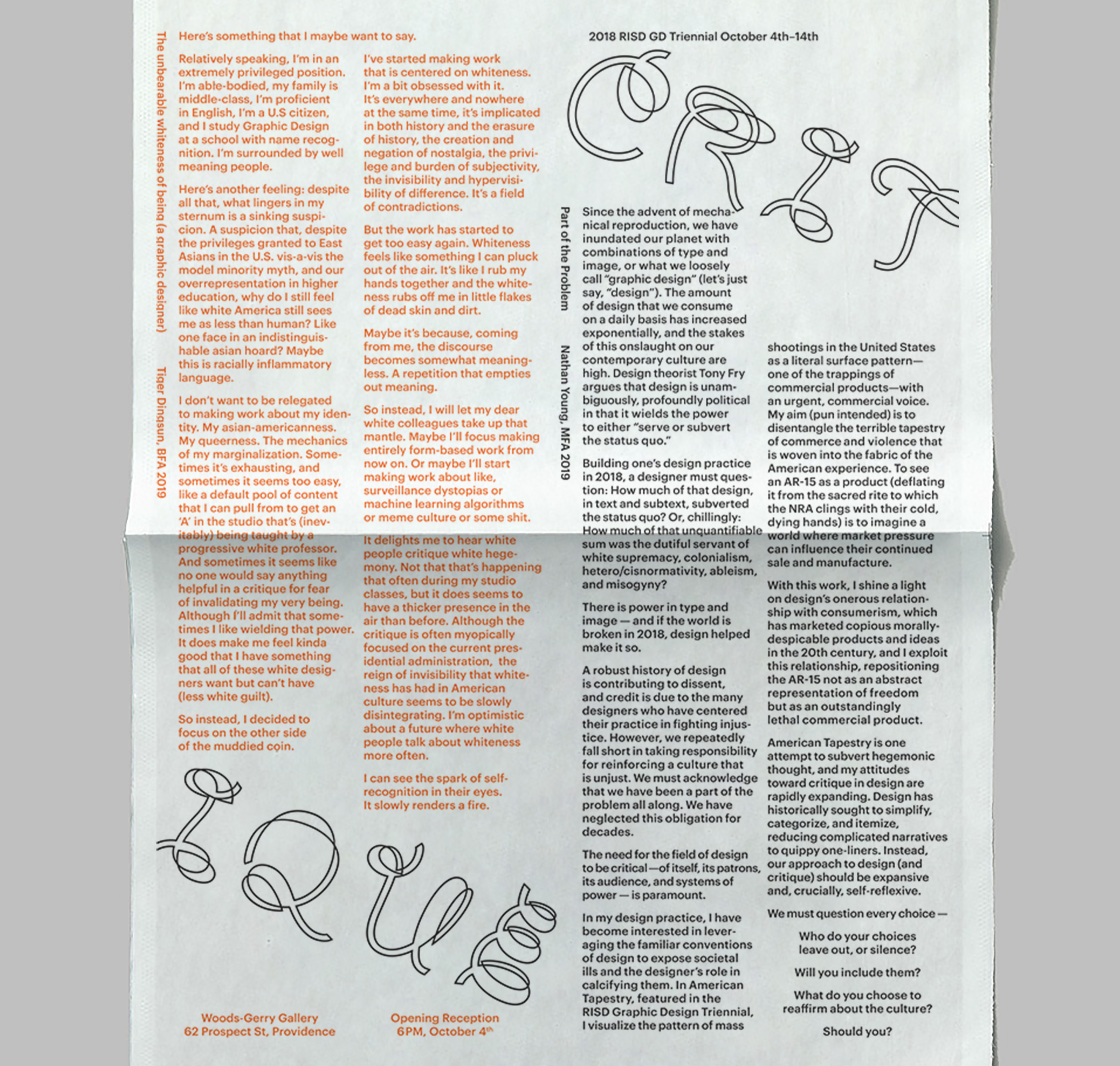

In my design practice I have become interested in leveraging the familiar conventions of design to expose societal ills and the designer’s role in calcifying them. In American Tapestry, featured in the RISD Graphic Design Triennial, I visualize the pattern of mass shootings in the United States as a literal surface pattern—one of the trappings of commercial products—with an urgent, commercial voice.

above: American Tapestry at the 2018 RISD Graphic Design Triennial, Woods-Gerry Gallery, Rhode Island School of Design

above: American Tapestry at the 2018 RISD Graphic Design Triennial, Woods-Gerry Gallery, Rhode Island School of DesignMy aim (pun intended) is to disentangle the terrible tapestry of commerce and violence that is woven into the fabric of the American experience. To see an AR-15 as a product (deflating it from the sacred rite the NRA clings to with their cold, dying hands) is to imagine a world where market pressure can influence their continued sale and manufacture.

With this work I sought to 1.) shine a light on design’s onerous relationship to consumerism, having marketed of all kinds of morally-despicable products and ideas in the 20th century and 2.) exploit this relationship, repositioning the AR-15 not as an abstract representation of freedom but as an outstandingly lethal commercial product.

My thinking around critique in design is rapidly expanding. Design has historically sought to over-simplify, reducing complicated narratives to quippy one-liners. Instead, our approach to design (and critique) should be expansive and, crucially, self-reflexive.

We must question every choice—

Who do your choices leave out, or silence? Will you include them?

What do you choose to reaffirm about the culture?

Should you?

--

Back

2018 RISD Graphic Design Triennial Publication

design by Annaka Olsen and Olivia de Salve Villedieu

2018 RISD Graphic Design Triennial,

curation and design by Goeun Park and Joel Kern

🦶

nathan dot young at temple dot edu